CO₂ dissolves in water to form carbonic acid (H₂CO₃), which dissociates in two steps to produce H⁺, HCO₃⁻, and CO₃²⁻ ions. The corrosion mechanism of CO₂ as a weak acid continues to be an area of active research.

In CO₂-containing solutions, four primary cathodic reaction mechanisms have been proposed:

H₂CO₃ Direct Reduction Mechanism: This is a commonly proposed mechanism. Although weak acid solutions (such as carbonic acid) and strong acids (such as hydrochloric acid) may have the same pH, the corrosion rate of metals in weak acid solutions is often higher than in strong acids. The reasons for this discrepancy are still under investigation.

In 1975, Dewaard et al. studied the anodic and cathodic reactions of X52 steel in CO₂-containing solutions using potentiodynamic polarization curves. They proposed the H₂CO₃ direct reduction mechanism, with the following reaction steps:

HCO₃⁻ Adsorption-Reduction Mechanism:

HCO₃⁻ ions in solution adsorb onto the anode surface and undergo reduction reactions, as follows:

HCO₃⁻ Adsorption-Reduction Mechanism:

HCO₃⁻ ions in the solution adsorb onto the anode surface and undergo a reduction reaction, as follows:

In this context, H_ads represents the hydrogen atom adsorbed onto the anode surface during the reaction. The reaction process is largely influenced by the diffusion of HCO₃⁻ ions. High concentrations of HCO₃⁻ can accelerate corrosion by facilitating the regeneration of H₂CO₃, as indicated by the following reaction:

2HCO₃⁻ → H₂CO₃ + CO₃²⁻

Water Reduction Mechanism: Linter et al. proposed that the reduction of H₂O or H⁺ in CO₂-containing solutions is more favorable due to the mass transfer limitations of HCO₃⁻ and H₂CO₃, which influence the rate of the cathodic reaction. Nesic et al. observed that under conditions of CO₂ partial pressure less than 100 kPa and pH ≥ 5, water undergoes a direct reduction reaction, as follows:

2H₂O + 2e⁻ → H₂ + 2OH⁻

Hydrogen Ion Reduction Mechanism: In strongly acidic solutions (such as HCl), the cathodic reaction typically proceeds as follows:

2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H₂

Due to mass transfer limitations, the rate of hydrogen evolution cannot exceed the rate at which H⁺ ions are transported from the solution to the metal surface. As a result, when the pH exceeds 5, the influence of this mechanism becomes negligible. Figure 8 illustrates the sulfide stress corrosion cracking (SSC) resistance of 17Cr material in a 20% NaCl solution at 25°C, following the NACE TM0177 Standard A method, with applied stress set to 90% of the nominal yield strength for 720 hours. When the pH exceeds 5, the hydrogen ion reduction mechanism has a minimal impact on the corrosion rate. However, when the pH falls below 4, it becomes the dominant cathodic reaction.

It should be noted that these mechanisms are interrelated, and pH is a crucial factor influencing the cathodic reaction. Zhu et al. proposed that as pH increases, the cathodic reaction gradually shifts from H⁺ direct reduction to H₂CO₃ direct reduction. In the pH range of 3.5 to 5.0, both reduction mechanisms operate in parallel and influence the overall reaction.

Bockris et al. were the pioneers in using the constant current transient method to derive the kinetic equation for anode precipitation and dissolution, based on pH and corrosion potential. They identified the overall reaction for the Fe electrode as: Fe → Fe²⁺ + 2e⁻. Furthermore, Bockris et al. outlined the sequence of anodic reaction steps from seven possible reaction mechanisms based on experimental data:

Fe + H₂O ⇌ FeOH + H⁺ + e⁻

FeOH → FeOH⁺ + e⁻

FeOH⁺ + H⁺ ⇌ Fe²⁺ + H₂O

It should be emphasized that the anodic reaction mechanism proposed by Bockris for strong acid environments is also applicable in CO₂ solutions. Recent studies have shown that pH significantly affects the anodic reaction mechanism. Nesic et al. used potentiodynamic scanning and constant current measurements to investigate the anodic reaction mechanism of X65 steel in CO₂ solutions. They observed distinct anodic reaction mechanisms in different pH ranges: pH < 4, 4 < pH < 5, and pH > 5, with a transition mechanism occurring between pH 4 and 5.

When pH < 4, the adsorption of OH⁻ and CO₂ is limited, and the anodic reaction proceeds as follows:

Fe + CO₂ ⇌ Fe²⁺

Fe²⁺ + H₂O ⇌ Fe₂OH⁺ + H⁺ + e⁻

Fe₂OH⁺ ⇌ Fe₂OH⁺ + e⁻

Fe₂OH⁺ + H₂O ⇌ Fe₂(OH)₂

Fe₂(OH)₂ ⇌ Fe₂(OH)₂

Fe₂(OH)₂ + 2H⁺ ⇌ Fe²⁺ + H₂CO₃

When pH > 5, the concentration of OH⁻ is high, while the presence of CO₂ is low. The anodic reaction steps are as follows:

Fe + CO₂ ⇌ Fe²⁺

Fe²⁺ + H₂O ⇌ Fe₂OH⁺ + H⁺ + e⁻

Fe₂OH⁺ ⇌ Fe₂OH²⁺ + e⁻

Fe₂OH²⁺ + H₂O ⇌ Fe₂(OH)₂ + H⁺

Fe₂(OH)₂ ⇌ Fe₂(OH)₂

Fe₂(OH)₂ + 2H⁺ ⇌ Fe²⁺ + H₂CO₃

In the reaction formulas above, Fe²⁺ represents a complex Fe–CO₂ compound, and the subscript "a" indicates adsorption on the anode surface. When 4 < pH < 5, the concentration of OH⁻ and CO₂ is low. The anodic reaction steps remain the same as when pH > 5, but the kinetic process differs. Nesic derived a comprehensive equation for the iron dissolution rate based on the anodic reaction mechanism:

izz = k * [OH⁻]^n * (PCO₂)^m

In this equation, izz represents the anode dissolution rate, k is a constant, and [OH⁻] is the hydroxide ion concentration in the solution (mol/L). The coefficients n and m are influenced by pH and PCO₂, with m being specifically affected by PCO₂. The anodic reaction mechanism discussed above remains valid today. It is noteworthy that some studies have found that bicarbonate ions also participate in the anodic dissolution reaction, accelerating the dissolution of iron in alkaline solutions. It is generally accepted that the dissolution of iron in alkaline solutions (pH > 7) occurs in both the pre-passivation and passivation ranges. Bicarbonate ions accelerate iron dissolution by chemically reacting with passivation layers (such as Fe(OH)₃ and Fe₂O₃) to form various soluble iron complexes. The reaction steps are:

Fe(s) + HCO₃⁻(aq) → FeHCO₃⁺(aq) + 2e⁻

FeHCO₃⁺(aq) → Fe₂(CO₃)₃(s) + CO₂(g) + H₂O(l)

Where (aq) represents the components in solution, and sol represents the components in the solid phase.

The overall process of the anodic reaction, M → Mⁿ⁺ + ne⁻, is well-established. However, in CO₂ solutions, the effects of CO₂ or carbonate on anodic dissolution and precipitation remain controversial and require further study.

In a CO₂ environment, H₂S significantly affects pipe integrity by influencing the uniform corrosion rate and causing stress corrosion cracking. The corrosion behavior of CO₂-resistant martensitic stainless steel seamless pipes in a CO₂/H₂S environment is largely determined by the stability of the passivation layer. Yan et al. compared the corrosion behavior of P110, 13Cr, and 22Cr in a CO₂/H₂S environment and found that the uniform corrosion rate of 13Cr falls between those of P110 and 22Cr. CO₂-resistant martensitic stainless steel seamless pipes can effectively block the transfer of corrosive ions by forming a chromium-rich passivation layer, thereby enhancing their corrosion resistance.

The stability of the passivation layer plays a crucial role in determining the uniform corrosion behavior of martensitic stainless steel in a CO₂/H₂S environment. Yan et al. compared the corrosion behavior of P110, 13Cr, and 22Cr in a CO₂/H₂S environment and found that the uniform corrosion rate of 13Cr falls between those of P110 and 22Cr. This is due to the following reasons:

- P110 does not contain sufficient chromium (Cr) and nickel (Ni), which inhibits the formation of an effective passivation layer. Its corrosion products primarily consist of iron carbonate and various forms of iron sulfide.

- Both 13Cr and 22Cr can form a passivation layer on the surface. The chromium-rich passivation layer prevents the transfer of corrosive ions, thereby protecting the metal from further corrosion. As the chromium content in the alloy increases, its resistance to uniform corrosion also improves.

The effect of H₂S on the passivation layer of 13Cr is temperature-dependent. Sakamoto et al. investigated the effect of H₂S partial pressure on the uniform corrosion rate of 13Cr in a CO₂/H₂S environment (Figure 9). The results indicate that:

- At temperatures of 150 ℃ and below, H₂S disrupts the passive film, leading to an increase in the uniform corrosion rate with higher H₂S concentrations.

- At temperatures above 200 ℃, the uniform corrosion rate decreases as H₂S concentration increases due to the formation of iron sulfide, which provides a stable protective effect on the surface.

Further research by Andrzej et al. indicates that:

- In the absence of H₂S, the uniform corrosion rate of 13Cr is governed by the passivation current density and increases with rising temperature.

- In the presence of H₂S, the uniform corrosion rate at low and medium temperatures continues to rise.

- The effect of H₂S diminishes with increasing temperature. At low and medium temperatures, the uniform corrosion rate of 13Cr increases markedly with higher H₂S concentrations. This is primarily due to the cathodic reduction of H₂S and the synergistic effect of HS⁻ ions, which promote additional anodic dissolution through adsorption.

Research on uniform corrosion in a CO₂/H₂S coexistence environment presents differing conclusions. Some studies suggest that the presence of H₂S can rapidly form a protective FeS layer, thereby delaying CO₂ corrosion in the presence of trace amounts of H₂S. Smith et al. developed a chart illustrating the minimum H₂S content required to delay CO₂ corrosion. However, other studies suggest that, in an acidic environment, galvanic corrosion occurs between the FeS-covered areas and the exposed regions, accelerating partial corrosion.

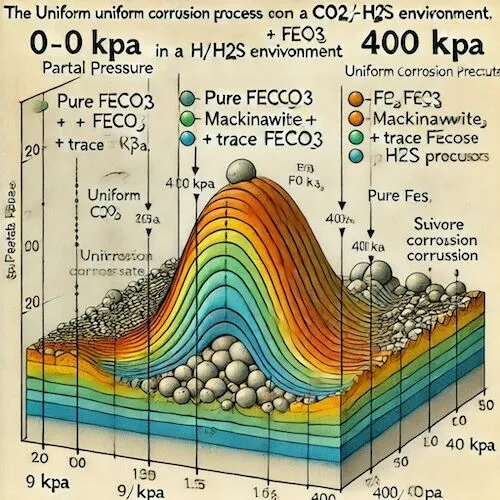

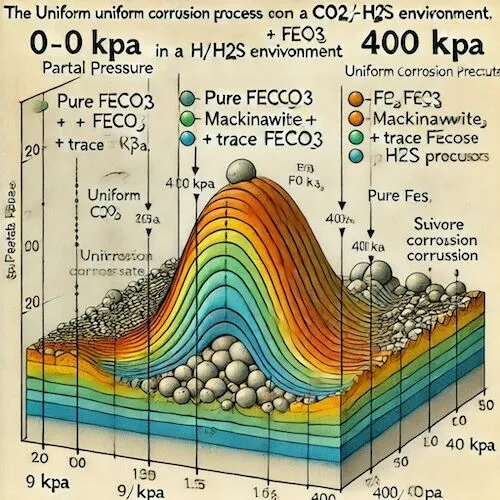

This disagreement arises because corrosion behavior in a CO₂/H₂S coexistence environment is influenced by factors such as temperature and pH, and varying test conditions can yield different results. Yan et al. studied the corrosion behavior of 3Cr-80 material under the following test conditions:

- Temperature: 90 ℃

- CO₂ partial pressure: 400 kPa

- pH: 6

- Rotational speed: 550 rpm

- Test duration: 7 days

The H₂S partial pressure was systematically varied from 0 to 400 kPa, and the results are presented in Figure 10:

As the PH₂S/PCO₂ ratio increased, the uniform corrosion process shifted from CO₂/H₂S joint control to H₂S control.

Corrosion product progression:

- Pure FeCO₃

- Mackinawite (FeS) + FeCO₃

- FeS + trace FeCO₃

- Pure FeS

In the presence of trace H₂S (PH₂S < 9 kPa), the protective effect of the corrosion products is enhanced, resulting in a uniform corrosion rate lower than that in a pure CO₂ environment. When the H₂S partial pressure exceeds 9 kPa, H₂S corrosion becomes the dominant cathodic reaction, and the uniform corrosion rate surpasses the level observed in a pure CO₂ environment. When the H₂S partial pressure exceeds 400 kPa, partial corrosion accelerates, leading to severe corrosion.

Figure 10

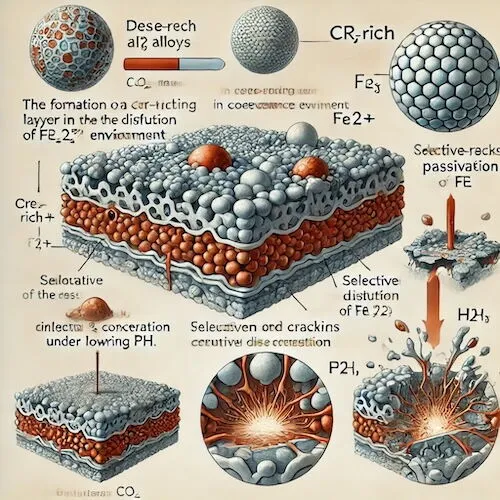

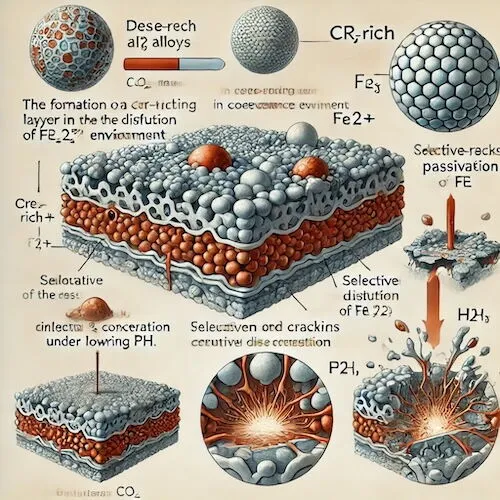

Partial corrosion of CO₂-resistant martensitic stainless steel seamless pipes in a CO₂/H₂S coexistence environment is primarily influenced by Cl⁻ concentration and pH; however, the effect of H₂S on partial corrosion requires further investigation. Wei et al. studied the partial corrosion behavior of P110, 3Cr, and 316L steels in a CO₂/H₂S coexistence environment and found that Cr-containing steels first undergo a solid-state reaction to form an initial corrosion product film composed of FeS (Mackinawite) and FeCO₃:

- Fe + H₂S → FeS + 2H⁺ + 2e⁻

- Fe + CO₂ + H₂O → FeCO₃ + 2H⁺ + 2e⁻

Subsequently, due to selective dissolution of Fe, Cr reacts to form a Cr-rich layer. When the Cr content in the alloy is high (e.g., in 3Cr and 316L), a dense Cr-rich layer forms on the material surface, which inhibits the diffusion of Fe²⁺, reduces Fe²⁺ concentration, and lowers the pH near the surface. This inhibits the deposition of FeCO₃. However, H₂S destabilizes the Cr-rich passivation layer, causing it to crack and peel, thereby accelerating partial corrosion. Furthermore, internal stress between the newly formed Cr-rich layer and the original passivation layer reduces stability, leading to cracking and peeling under the influence of the flowing solution, which ultimately induces partial corrosion. The corrosion mechanism is illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11: Pitting behavior of Cr-containing alloys in a CO₂/H₂S coexistence environment

For stainless steels with self-passivating properties, low levels of dissolved oxygen can reduce passivation characteristics, altering their corrosion resistance. Yue et al. studied the effect of dissolved oxygen (ranging from 10 to 1,000 µg/L) on the surface passivation performance of super 13Cr stainless steel in a CO₂/H₂S environment. The results showed that both the pitting effect and pit size increased with higher dissolved oxygen concentrations in the CO₂/H₂S solution. Dissolved oxygen significantly destabilizes the passivation film, increasing the risk of partial corrosion. Under saturated CO₂ conditions, higher dissolved oxygen concentrations increase the number of available electron acceptors on the electrode surface. Once the electrode surface reaches its self-corrosion potential, the material’s stability and passivation characteristics are lost. In the presence of H₂S, higher dissolved oxygen concentrations promote the adsorption of sulfur atoms with higher surface activity on the 13Cr surface, leading to partial corrosion even at trace dissolved oxygen levels (100 µg/L).

To conclude, the corrosion mechanism of CO₂-resistant martensitic stainless steel seamless pipes arises from the complex interaction between CO₂ and H₂S. Optimizing material design and manufacturing processes enhances the production efficiency of these pipes. They exhibit superior performance in high-temperature, high-pressure, and corrosive environments, fulfilling the stringent service requirements of oil and gas fields.